Implementation of the deep changes demanded depends on our ability to write a new story, a utopian one for sure, but one which is in accordance with and based on the reality in which we live.

Ove Jackobsen

Prof. Ove Jakobsen teaches ecological economics at Nordland University in Bodø, Norway and the co-founder and leader of the Centre for Ecological Economics and Ethics. His interest in alternative economic thinking developed in 1987 when he wrote his book Environment, Myths and Marketing. In the following years and encouraged by many forward-thinking economists and researchers, he would come to deepen his thinking by developing anthropsophical and phenomenological foundations which allowed him to develop the transdiciplinary perspectives needed for the advancement of ecological economics, a subject he has been teaching for over twenty years.

Photo: Simon Robinson

The most important elements of Jakobsen’s work was developed in partnership with Stig Igebrigsten (Bodø Graduate School of Business) and Knut J. Ims (the Norwegian School of Economics). These were complemented by additional research into Buddhist-inspired economic thinking and practice and more recently through many inspirational conversations with his friend Fritjof Capra. All of these elements have been integrated in the publication in April of his new book Transformative Ecological Economics: Process Philosophy, Ideology and Utopia (Routledge, London) which forms part of the series Routledge Studies in Ecological Economics.

The central argument of ecological economics is that we need to make a shift from the ‘green’ economy, which only focuses on reducing negative symptoms to save the existing neo-classic economic paradigm, to a new economic paradigm rooted in an organic worldview. While there are now a number of authors who have published works on this theme, few have built their arguments around an ontology of process philosophy. It is for this reason I would like to locate Transformative Ecological Economics into a lineage of books which includes our own book Holonomics: Business Where People and Planet Matter, Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi’s The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision, and Tor Hernes’ A Process Theory of Organization (all three of which we published, incidentally, in 2014).

Photo: Simon Robinson

Transformative Ecological Economics is structured in three clear parts. The first part provides the context for interpretation, starting with an introduction to the philosophical foundations of Alfred North Whitehead’s process philosophy, which for many, including Jakobsen, is able to ingrate both western intellectual thinking and Eastern spirituality. Jakobsen introduces Whitehead with Latour’s comparison of his philosophy to whale-watching, in which a person can spend all day seeing nothing and then suddenly the whale appears and blows, only to disappear suddenly again. Jakobsen writes:

Whitehead wanted his theories to perform a social function and to make human life richer and more meaningful by helping us to understand experiences in a more dynamic way. Instead of constructing the task of science to be that of overcoming subjective illusion in order to reach objective reality, as many modern thinkers have done, Whitehead takes the speculative risk of defining nature as “quite simply [as] what we are aware of in perception” (Segall, 2013). Whitehead’s scientific method can be compared with Goethe’s gentle empiricism which rejected simple mechanical explanations and pursued instead nature’s reasons by learning to participate more fully in the archetypal patterns interwoven with experience itself. One of the the main differences between mechanistic and organic models is that “a machine can be controlled, a living system can only be disturbed (Capra and Luisi, 2014).

I am extremely happy that Fritjof was able to introduce me to Ove, as this single paragraph shows how both Holonomics (which has as its ontological foundation Goethe’s approach to process philosophy) and the systems view of life of Fritjof and Pier Luigi Luisi. Whitehead’s philosophy sees the world as organic, and nature as a “structure of evolving process”. To help explain this, Jakobsen cites Capra and Luisi’s observation that “the sharp Cartesian division between mind and matter, between the observer and the observed, can no longer be maintained”. As Jakobsen notes, “How to bridge the gap between how we experience the world and speak of it is the essential problem”.

Photo: Simon Robinson

Maria and I work with Goethe’s work on colour and prisms to help people enter into the experience of becoming, and to develop our understanding of process philosophy. A second way we are working is with Fritjof as part of his on-line course Capra Course, which was created to take people into the systems view of life. I shall return to the theme of education in relation to process philosophy, but it is important to cover this in detail, especially as the shift in our thinking which ecological economics demands involves a paradigm change, to one where “relations become more important than objects” and where “every organism is constituted by its connections to other organisms”. This is the shift into understand life as being arranged in networks, one of the major insights of Fritjof’s work, leading to the insight that “A system’s resilience will increase as the pattern of interconnections becomes more complex”.

Whitehead’s philosophy is not one of nested hierarchies, seeing parts as categorical members of larger groupings. Rather “the whole is emerging from its parts, and the parts are emerging within the whole”. To make this more concrete, Jakosen highlights the importance in terms of the way in which we understand the way in which human stengths and virtues must be “cultivated in a cultural context”. From here, the discussion develops by exploring Whitehead’s conception of creativity, a term he used to describe “the inherent tension between actuality and potentiality”.

The endpoint of the introduction to Whitehead is his general definition of a civilised society “as exhibiting the qualities of truth, beauty, adventure, art and peace”. This can be compared to neo-liberal economics which “postulates atomistic competitive markets constituting of autonomous actors”. The antidote to this outdated and mechanistic world view is one of a civilised society “based on organic interdependence” where economics is characterised “by cooperation instead of ruthless competition”.

The main focal point of Transformative Ecological Economics is the role which utopias play, which are “usually constructed against a background of severe problems or crises in the current society”. The idea is to explore phenomena from a new perspective in order to discover things we did not see previously. Utopias connect with Whitehead’s philosophy in terms of providing “an expression trascending (potentiality) the description of reality (actuality).” This tension between what is and what could be is therefore “of vital significance for change processes”. Ecological economics therefore “represents a utopian description of alternative development based on critical reflections on contemporary society and economy”.

Jakosen concludes that “utopia is an agent for change” whereas the ideology of green economics is “is to maintain stability”. This allows him to create a demarcation between green economics as ideology and ecological economics as utopia. I think one of the most striking shifts of perspective comes from seeing products as isolated items without ethical dimensions, to the ecological economics perspective where “values are inherent in the processes” and which therefore sees products interpreted as “an integrated part of social and environmental systems:

Based upon the philosophy of organism, the “product” concept is understood holistically, emphasizing the processes which are necessary parts of the creation, distribution, using and recirculation of a product. Thus we suggest taking a more extended view which encompasses the space and time dimensions of the product in terms of when and where it grew, who were the growers, taking the quantity of (artificial or natural) fertilizer used, asking which means of transportation was used, and what the profit margin in all the stages of the value chain was.

In Part II of Transformative Ecological Economics Jakobsen provides an overview of some of the most important contributors to ecological economics, from the beginning of the twentieth century until today. Jakobsen identifies four main sources of inspiration in the historicalprocess which led to the development of ecological economics – thermodynamics, evolutionary theory, anthroposophy and Buddhism.

All of the perspectives were chosen in order to provide contributions to the development of a utopian perspective which makes it possible to “move outside of the established ideology to get a better understanding of the current situation and inspiration to develop realistic processes based on knowledge and insight”. Jakobsen provides his utopia in part three, but makes the important point that “working with utopian narratives is a process, not an objective method for finding the correct solutions to concrete problems”. The narrative Jakobsen develops is therefore based in part on “descriptions of reality as it exists and partly on the interpretations that influence our understanding of reality”.

In a recent dialogue with Fritjof Capra, published by Sustainable Brands, we discussed the fact that one of the great questions of recent times is how to scale up the appreciation and understanding of ecological economics. With humanity facing so many systemic issues, many organisations and businesses are now realising that their current way of thinking and operating is no longer working in our volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. The question therefore is how to rapidly develop within people a profound capability in systems thinking, and in a manner which can be rapidly scaled up to many thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of people.

As Fritjof noted in this dialogue, there are major implications of ecological economics for our educational system, and in particular, consequences for our universities, which are not currently structured to teach students how to solve our world problems in a systemic or transdisciplinary manner. Having thought about this problem for many years, in 2015 he had the idea to create Capra Course, an online course where people from many different walks of life and academic backgrounds can come together to discuss all of these themes in a holistic manner.

Like Fritjof, Jakobsen promotes the need for cross-disciplinary dialogues in the scientific community, in order to overcome the atomisation of knowledge which has arisen due to the nature of specialised scientific research. He also states that “it is necessary to include art in the dialogue because it is vital to discover and communicate knowledge and wisdom through art”.

Credit: Capra Course

Having been involved in the development of Capra Course from the start, it has been a very amazing experience to have participated in many such transdiciplinary dialogues. People who take part in Capra Course come from many different backgrounds, including the art and design world, and a recent open letter to Fritjof from artist and designer Susan Umbenhour shows just how powerful the experience of mixing art with the science of systems thinking can be. In her letter, Susan wrote:

A major shift has occurred within me as an artist while listening. Initially, my intent was to reconfigure my own artistic process, but with each new lecture, my process was transforming itself so quickly, I decided to wait, absorb it all, and let it come forth on its own. As I continued, I found each lecture fascinating often listening more than once to clarify and understand an integration and exchange of systems – essentially, the network, the characteristics of the cell and how it sets the stage for interdependence. I now have a renewed sense of purpose as a designer.

Capra Course offers participants a three-month long exploration with Fritjof of the many different features of the utopia which Jakobsen describes:

- Worldviews and ontologies

- Economic systems

- Change processes

- VSO (Viable Organic Society)

- Circulation economics

- Business practices

- Authenticity

- The image of man

As Jakobsen notes, almost all of the thirty different perspectives discussed in part II “point to the necessity of re-establishing economic theory and practice with an organic ontology”. The utopia he presents links is presented in the following four different levels:

- Metaphysics; Organic worldview

- Economic system; Circulation economics

- Business practice; Partnership approach

- Image of man; Ecological man

He concludes with the argument that:

…change must be implemented on all levels at the same time, ontology must be part of the curriculum at universities and business schools, alternative economic systems must be developed based on ontological preconditions, business practice must find a balance between society and nature and we must get rid, once and for all, of the idea of economic man.

I do believe that Jakobsen’s utopia is now not only something which exists as a narrative in academic circles, but is now becoming a reality through a number of initiatives which are aiming to create a new generation of business tools, techniques and methodologies which are authentic as well as sustainable, and which are based on systems thinking and organic ontologies.

I am a member of the Strongly Sustainable Business Model Group which is based on the Strategic Innovation Lab of OCAD University in Toronto, Canada. The group has members who are working on a wide range of related initiatives, and these are helping shape a more systemic approach to business. Examples include the Flourishing Business Canvas, Future Fit Benchmark, the Reporting 3.0 platform and our own framework Customer Experiences with Soul.

Flourishing Business Canvas

A traditional business model describes how an organization creates and delivers financial value. The Business Model Canvas and the ontology behind it created by Alex Osterwalder brings together the value proposition, customer segments, customer relationships, channels of contact with the market, resources, activities and partnerships. These result in costs and revenues.

The benefits of Business Model Canvas reside in being a visual tool that with nine questions defines a Profitable Business Model, emphasizing the financial dimension. In the case of Flourishing Business Canvas the objective is to define a Sustainable Business Model considering two other dimensions, the environmental and the social as well as the financial. Thus, there are sixteen questions which systemically describe a sustainable and authentic Business Model.

The Flourishing Canvas is published with permission from FlourishingBusiness.org

The Flourishing Business Canvas was conceived and developed by Antony Upward, and based on three-years of research and an extensive organic and systemic ontology: An Ontology for Strongly Sustainable Business Models: Defining an Enterprise Framework Compatible with Natural and Social Science

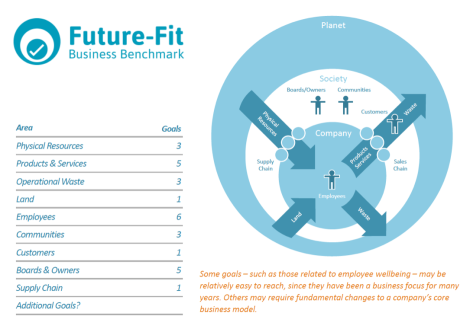

Future Fit Benchmark

Credit: Future Fit Institute

The Future Fit benchmark which was created to answer the two following questions: How would we know a future‑fit business if we saw one? and How can we tell how far away a business is from being future‑fit? The Future Fit Benchmark takes a systemic approach to understanding both social and environmental issues we are facing today, all of which are interconnected. The model created builds on 25 years of research from the natural and social sciences, one of the primary sources being that research lead by the founders of The Natural Step.

The complete Future Fit Benchmarking Tool can be downloaded here. In addition to Geoff Kendall and Bob Willard, the tool was developed with key contributions and strategic advice from Pong Leung, Chad Park, Martin Rich, Antony Upward and Saralyn Hodgkin. It is being developed in an iterative process, with many individuals and organisations contributing to the development process. Future research will look at what it would mean for a household to be future-fit? Or a city? Or a university?

Reporting 3.0

Reporting 3.0 which is a platform designed to help catalyse the development of a new form of business reporting to spur the emergence of a regenerative and inclusive global economy. One of their projects is looking what a new accounting would like twenty years from now and involves defining the parameters of a new, comprehensive discipline of accounting that encompasses financial accounting, management accounting and sustainability accounting.

Customer Experiences with Soul

As I wrote in my recent article for Schumacher College, customer experience design is the forgotten dimension of sustainability. The first third of Holonomics is dedicated to the dynamics of seeing, and the reason is that experience and the phenomenological elements of process philosophy now play a fundamental role in ecological economics.

Our Customer Experiences with Soul framework describes how our holonomics approach can be applied to the area of customer experience design. One of the central tools is the Holonomic Circle, which is based on a philosophical foundation of both hermeneutical phenomenology and systems thinking, and which articulates the meaning of soul in a design, business and branding context.

Source: Customer Experiences with Soul: A New Era in Design

It provides a holistic framework for designers, corporate entrepreneurs, creative leaders and those starting a new business or initiative to explore the principles underlying the dynamics of soulful customer experiences. It applies not only to the design of customer experiences, but also to product and service development, organisational design, branding, communications, leadership, training and strategy. It does so by linking the tools, techniques and framework for developing customer experiences with soul with an exploration of the questions of authenticity, purpose and human values.

One of the elements which Maria and I have introduced to the Capra Course alumni network are regular masterclasses. These one-hour sessions are designed to talk through the many different aspects of how to put the systems view of life into practice in organisations, with Maria and I sharing many insights and practices based on our many years of doing so in a business environment. These include discussions of tools such as the Flourishing Business Canvas, the Future Fit benchmark and methodologies such as Balanced Scorecard which have a basis in systems thinking and which are designed to change the way of seeing in organisations.

One of the main objectives of Transformative Ecological Economics was to show the “fundamental interplay between human activity and environmental conditions”. As Jakobsen writes,”the consequences of abstracting economics out of nature and society is “lifeless” concepts, theories and models. Economics deprived of emotion and value is reduced to no more than a mishmash of numbers and statistics”.

By integrating Whitehead’s organic ontology with a dynamic conception of utopia, Jakobsen shows how deep systemic change can be possible through teaching a new narrative in which civilisation develops based on cooperation with considerable numbers of people working together for common ends. This change depends on creativity, with the process of our evolution, our becoming, developing in the tension which exists between actuality and potentiality. Through deep learning experiences such as Capra Course and through the most advanced and innovative business tools and initiatives, this utopian vision is now starting to help business shift their thinking from pure economic growth to a richer, more flourishing worldview of ecological economics – interconnected, systemic, ethical and creative.

Related Articles

How to Scale Up Systems Thinking: The Evolution of Fritjof Capra’s Capra Course

On Art and Systems Thinking: An Open Letter to Fritjof Capra

Implementing Systems Thinking in Organisations: Capra Course Alumni Network Masterclasses

Excellent post Simon. I was not aware of Ove Jakobson’s work and can see how it complements Frijtof’s and your own. I’m intrigued by the ontology of process philosophy and will read further on this as it’s clearly the foundation for the integrative view you’re holding.

Hi Stephen,

Thanks for your comment. In terms of our Holonomics approach, we do have a process philosophy foundation, but our focus is putting this into practice. As many commentators have said, process philosophy is extremely difficult to grasp, especially if it is only an academic or intellectual approach. We have a lot of experiences and have designed many exercises to help people experience the insights and therefore develop an expanded level of consciousness. When people are able to reach an intuitive understanding, that is when the internal (personal) changes happen, and you start to live the philosophy as opposed to just discussing it. If you do happen to read Holonomics, you will see this more practical approach, which we combine with our teaching (both courses and consultancy work).

gostei muito e continuarei acompanhando as publicações,muito boa,vou voltar sempre.

Muito obrigado, abraços

Pingback: Fritjof Capra on Communities and Flourishing Business Models | Transition Consciousness·

Pingback: A Conceptual Framework for Ecological Economics Based on Systemic Principles of Life | Transition Consciousness·